INTRODUCTION

This is a development of the unique reference information assembled by Morag-Anne Elder, Lynn Morrison and Charles Gore. The hardback version was edited by Charles Gore and published in 1994, listing the contents of the printed collections of Scottish instrumental music of the 18th and 19th centuries. The Traditional Music Index is the only reference source for the titles of Scotland’s original dance tunes and song airs brought together and fully cross-referenced in one complete listing. The earliest collections of this music were published around 1700 and were the product of London-based printing houses. Edinburgh followed suit from 1730, in a small but expanding degree through the 1760s and 70s, leading up to the boom years of the Golden Age of Scottish dance (1780-1830) during which time about 300 volumes of the best of Scotland’s dance music and song airs were issued by a number of publishers, mostly in Edinburgh and Glasgow, a few in London, Perth and Aberdeen. They constitute what was declared at the time to be one of the finest examples of “people’s music” in Europe. This reputation was enhanced by the presence in the repertoire of many of the lovely melodies (many of them dance tunes) that were destined to achieve immortality in settings of the poetry of Robert Burns and to remain national favourites, perhaps for all time. The Index continues through the era of the great compilations of dance music (c1870-1900) which were to be the popular source-books for the traditional dance repertoire of the 20th century and concludes with the complete published output of the fiddler-composer James Scott Skinner (1848-1927). His career was firmly established in the 19th century, yet it forms a bridge with the first half of the 20th century and the arrival, in the 1950s, of the modern folk movement with its distinctive internationality. The style of the Scottish dance repertoire composed since 1900 has remained remarkably faithful to its earlier counterpart, despite the arrival of the accordion in the 1920s and the wholesale adoption of bagpipe music by dance bands from the 1930s. An Index has to have a cut-off point. The period 1935-50, with World War II at its heart, was a relatively quiet phase that ended with the tempestuous march to popularity of music from Shetland and Ireland. The older repertoire is still in performance and is being “re-discovered” by players of all ages as it becomes more widely accessible again.

300 years of Tradition

1690-1730 Over these early years it became fashionable to include dance music “in the Scottish taste” in collections of popular dance music published in London. The Playfords and their imitators were early on the scene. John Young published in London “A Collection of Scotch Tunes for the Violin” (1720).

1730-1770 In these years the first collections of dance music were published in Edinburgh and became increasingly popular. They should not be confused with the plethora of little dance manuals popular in London and mostly printed there throughout the same period. Robert Bremner (1757-61) may have been the first to include “Reels” in the title of a collection. John Riddle (Riddell) of Ayr published his own compositions in 1760.

1770-1830 The great flood of dance music publications continued for more than fifty years, reaching its peak in the 1790s, when fiddler-composers such as the Gows, the Mackintoshes, Alexander MacGlashan, Robert Petrie, Malcolm Macdonald, Simon Fraser – and probably more than 100 others - were publishing collections of their own compositions often interspersed with the popular favourites of their day. Patronage was gladly given to these would-be publishers and there was never a shortage of subscribers.

1870-1900 For about thirty years, during which time the great James Scott Skinner rose to fame as teacher, composer and performer, a number of dedicated collectors, James Kerr, James Stewart Robertson and their like, published very large compilations of dance music, almost all strathspeys and reels arranged in medley form, with a smattering of jigs and country dance sets. These became the source material for the dance bands of the following century and many are still in print. These principal libraries hold music collections:

Aberdeen University and Public Libraries (J Murdoch Henderson)

Dundee Public Library (A.J.Wighton Collection, which has an index online)

Edinburgh: National Library of Scotland (Glen, Inglis, J Murdoch Henderson)

Glasgow Mitchell Library (Frank Kidson Collection)

London, The British Library (see Catalogue of Printed Music, CPM)

Oxford, The Bodleian Library (Walter Harding Collection, Scottish Dance section)

Perth, A.K. Bell Library (The Athole Collection bequest)

An e-mail to the National Library of Scotland (or, if not held there, one of the other national library sources) quoting Title, Volume and Page, along with the appropriate payment (which may vary considerably according to the age of the publication) will normally result in a copy being sent. Prices also vary from Library to Library. A growing number of the older collections are now coming back into print or are available as e-books. Good sources for new editions are Highland Music Trust (Inverness), Taigh na Teud (Skye) and Hardie Press (Edinburgh).

The List of Sources aspires to be inclusive as far as the printed fiddle collections are concerned. Inevitably, there are omissions; the old collections may announce “Book First” when there are no succeeding volumes. In cases where no mention is made of an intended series, Book Two (and more) have been discovered. Forgotten volumes are sure to appear in future, but these can now be assimilated into the list as they emerge. Sheet music (publications of four to eight pages with or without title page) was never meant to be included. It was published in profusion throughout the 18th century and well into the 19th and usually re-appears in one or more of the bigger collections, but there are exceptions and forgotten gems will continue to surface. Other choices had to be made: The London-published dance manuals fall into two categories: those that are heavily biased towards English dance and those that are essentially Scottish. Song collections with words, both Gaelic and Scots and “songs without words” have been excluded unless they contribute otherwise unpublished content. Irish dance music of the same period, historically a separate study and well documented in Ireland, has been excluded except where it occurs alongside its Scottish equivalent. Dance music from the military pipe manuals, widely popular since the 1930s among Scottish players has already been comprehensively listed and would have doubled the size of the Index, which nevertheless runs to over 12,000 titles.

The Tune Title Index (A-Z) lists the Theme Code (see below), the key and time signatures and the Source Code, which also indicates in how many collections a tune has been published. Example: A1V1P1 stands for AIRD, James, Volume 1, Page 1 and the same pattern follows through the source listing. Where available, further details are given - composer, library source, issue date. The codes are essential to the all-round functioning of the Index.

Additional Search Options The online version has a number of advantages over a printed index. You can download and print out the whole contents of collections and perform word-search and part-title searches. Lists can be assembled of music by time or key signature and can refer to special comments such as occur alongside tunes in the original collections - Slow, Slow Strathspey, Irish, Old, etc. etc. These comments were almost universally excluded by compilers in the later 19th century when so many old strathspeys and reels were re-published.

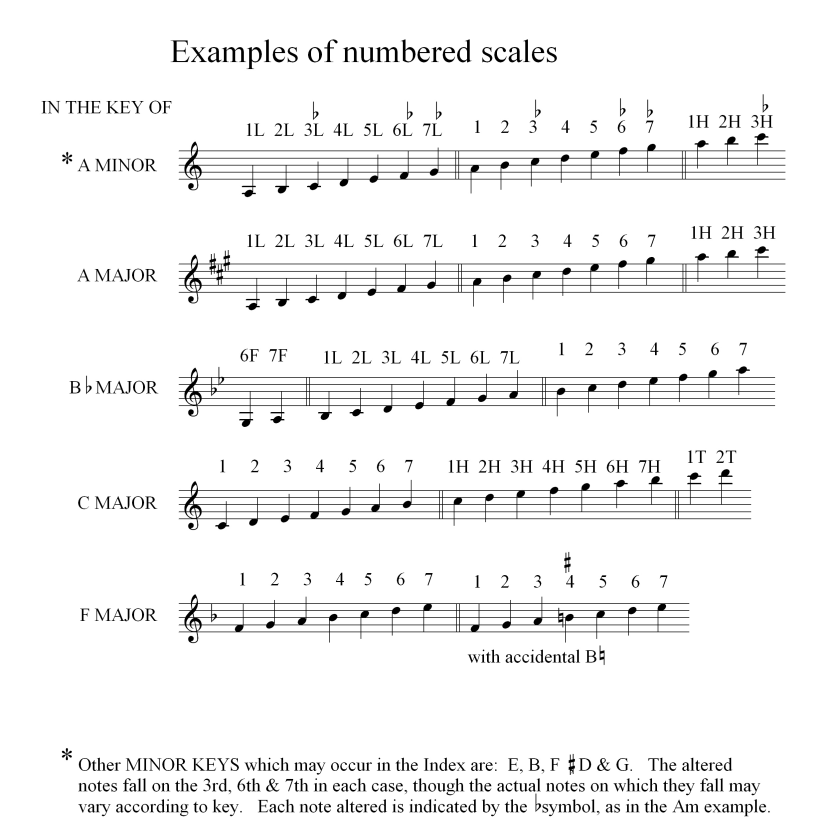

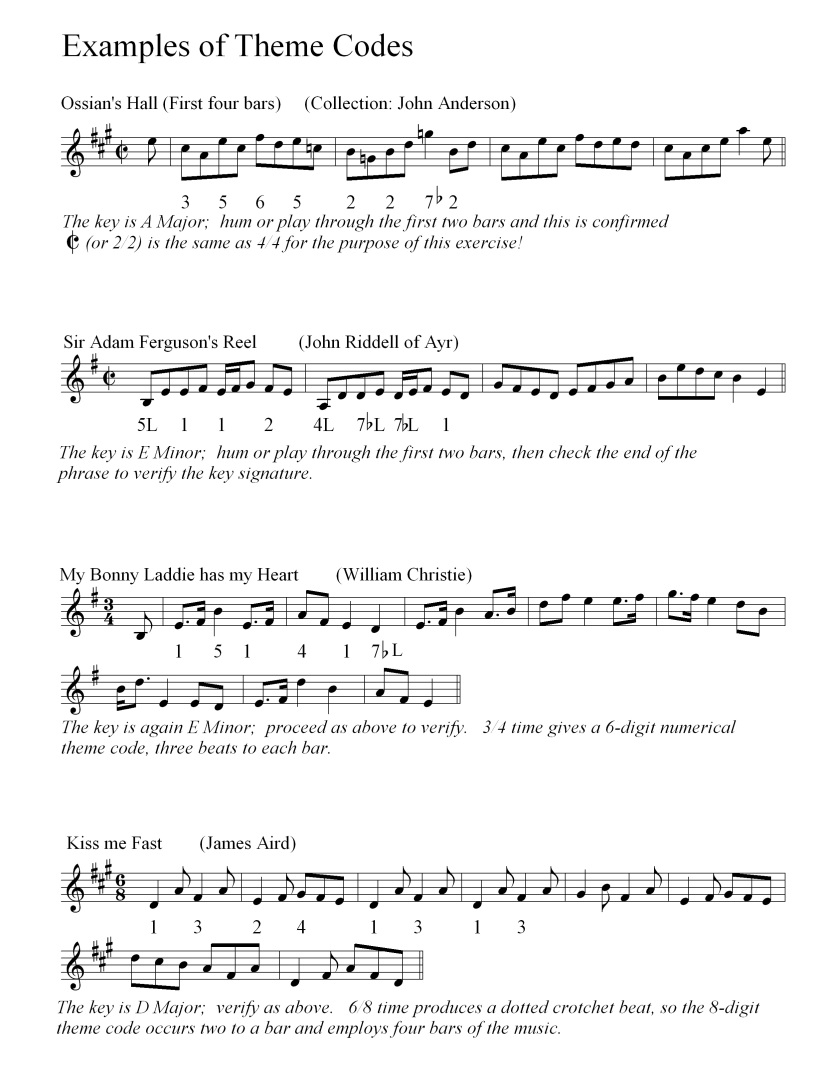

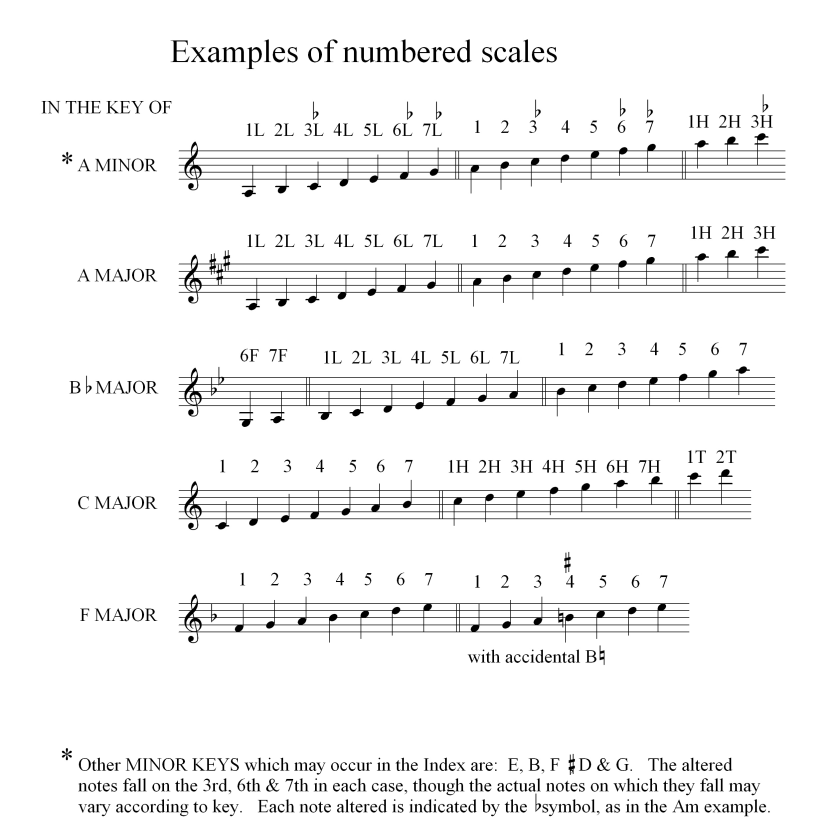

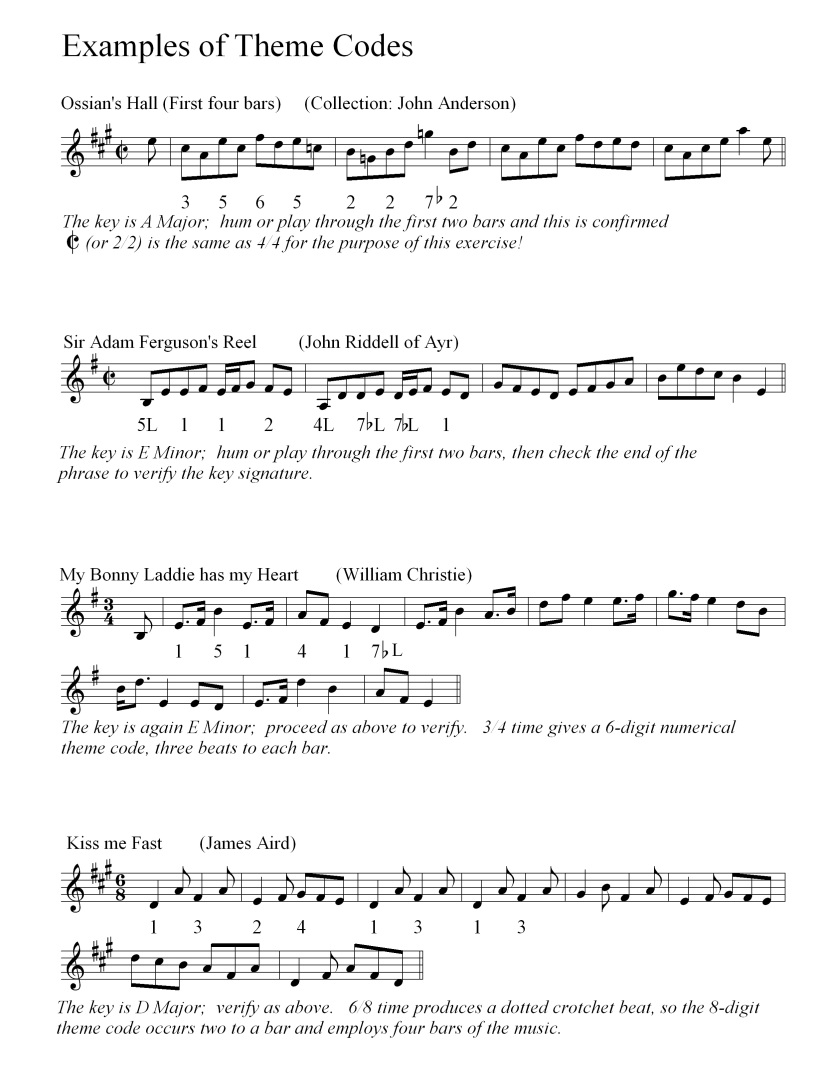

The Theme Code Index has the primary function of cross-referencing tunes that have acquired more than one title down the years. It reads in numerical sequence from 1-7 for the middle octave; 1L is the lowest listed beat note in the octave below middle C; 1H indicates one octave above and (less frequently) 1T, two octaves above. However many keys the tune has been set in over the years, the key note always has the number 1, so the pattern of the code remains the same. It is based on the Beat Notes of the first two, three, or four bars of the tune: 4 to the bar for common time, 4/4 and 2/2; two to the bar (6/8, 2/4); three to the (3/4), and so on. Special symbols are used to signal the minor mode and accidentals (b, #), and rests (0). Versions of tunes may vary to some degree. The ultimate use for the Theme Code Index is to find a tune of which the melody is remembered but none of its titles. Initially this requires a little practice, jotting down the first bars of the tune and setting the numbers in order, but in most cases it soon becomes a simple routine. For example: The two-part code 3155 551H2H represents one version of one tune, the old song air “Polwart on the Green”. CODE A leads to the area of the list in which it may be found and CODE B completes the identity of the tune. In some cases, there will be other claimants to the code which may include tunes with the same beat notes but a fundamentally different melodic structure. For some reason this has no effect on the efficiency of the system itself.

Anyone wishing to use the Index Online for constructing Theme Codes should go to our Theme Coding page.

This is a development of the unique reference information assembled by Morag-Anne Elder, Lynn Morrison and Charles Gore. The hardback version was edited by Charles Gore and published in 1994, listing the contents of the printed collections of Scottish instrumental music of the 18th and 19th centuries. The Traditional Music Index is the only reference source for the titles of Scotland’s original dance tunes and song airs brought together and fully cross-referenced in one complete listing. The earliest collections of this music were published around 1700 and were the product of London-based printing houses. Edinburgh followed suit from 1730, in a small but expanding degree through the 1760s and 70s, leading up to the boom years of the Golden Age of Scottish dance (1780-1830) during which time about 300 volumes of the best of Scotland’s dance music and song airs were issued by a number of publishers, mostly in Edinburgh and Glasgow, a few in London, Perth and Aberdeen. They constitute what was declared at the time to be one of the finest examples of “people’s music” in Europe. This reputation was enhanced by the presence in the repertoire of many of the lovely melodies (many of them dance tunes) that were destined to achieve immortality in settings of the poetry of Robert Burns and to remain national favourites, perhaps for all time. The Index continues through the era of the great compilations of dance music (c1870-1900) which were to be the popular source-books for the traditional dance repertoire of the 20th century and concludes with the complete published output of the fiddler-composer James Scott Skinner (1848-1927). His career was firmly established in the 19th century, yet it forms a bridge with the first half of the 20th century and the arrival, in the 1950s, of the modern folk movement with its distinctive internationality. The style of the Scottish dance repertoire composed since 1900 has remained remarkably faithful to its earlier counterpart, despite the arrival of the accordion in the 1920s and the wholesale adoption of bagpipe music by dance bands from the 1930s. An Index has to have a cut-off point. The period 1935-50, with World War II at its heart, was a relatively quiet phase that ended with the tempestuous march to popularity of music from Shetland and Ireland. The older repertoire is still in performance and is being “re-discovered” by players of all ages as it becomes more widely accessible again.

300 years of Tradition

1690-1730 Over these early years it became fashionable to include dance music “in the Scottish taste” in collections of popular dance music published in London. The Playfords and their imitators were early on the scene. John Young published in London “A Collection of Scotch Tunes for the Violin” (1720).

1730-1770 In these years the first collections of dance music were published in Edinburgh and became increasingly popular. They should not be confused with the plethora of little dance manuals popular in London and mostly printed there throughout the same period. Robert Bremner (1757-61) may have been the first to include “Reels” in the title of a collection. John Riddle (Riddell) of Ayr published his own compositions in 1760.

1770-1830 The great flood of dance music publications continued for more than fifty years, reaching its peak in the 1790s, when fiddler-composers such as the Gows, the Mackintoshes, Alexander MacGlashan, Robert Petrie, Malcolm Macdonald, Simon Fraser – and probably more than 100 others - were publishing collections of their own compositions often interspersed with the popular favourites of their day. Patronage was gladly given to these would-be publishers and there was never a shortage of subscribers.

1870-1900 For about thirty years, during which time the great James Scott Skinner rose to fame as teacher, composer and performer, a number of dedicated collectors, James Kerr, James Stewart Robertson and their like, published very large compilations of dance music, almost all strathspeys and reels arranged in medley form, with a smattering of jigs and country dance sets. These became the source material for the dance bands of the following century and many are still in print. These principal libraries hold music collections:

Aberdeen University and Public Libraries (J Murdoch Henderson)

Dundee Public Library (A.J.Wighton Collection, which has an index online)

Edinburgh: National Library of Scotland (Glen, Inglis, J Murdoch Henderson)

Glasgow Mitchell Library (Frank Kidson Collection)

London, The British Library (see Catalogue of Printed Music, CPM)

Oxford, The Bodleian Library (Walter Harding Collection, Scottish Dance section)

Perth, A.K. Bell Library (The Athole Collection bequest)

An e-mail to the National Library of Scotland (or, if not held there, one of the other national library sources) quoting Title, Volume and Page, along with the appropriate payment (which may vary considerably according to the age of the publication) will normally result in a copy being sent. Prices also vary from Library to Library. A growing number of the older collections are now coming back into print or are available as e-books. Good sources for new editions are Highland Music Trust (Inverness), Taigh na Teud (Skye) and Hardie Press (Edinburgh).

The List of Sources aspires to be inclusive as far as the printed fiddle collections are concerned. Inevitably, there are omissions; the old collections may announce “Book First” when there are no succeeding volumes. In cases where no mention is made of an intended series, Book Two (and more) have been discovered. Forgotten volumes are sure to appear in future, but these can now be assimilated into the list as they emerge. Sheet music (publications of four to eight pages with or without title page) was never meant to be included. It was published in profusion throughout the 18th century and well into the 19th and usually re-appears in one or more of the bigger collections, but there are exceptions and forgotten gems will continue to surface. Other choices had to be made: The London-published dance manuals fall into two categories: those that are heavily biased towards English dance and those that are essentially Scottish. Song collections with words, both Gaelic and Scots and “songs without words” have been excluded unless they contribute otherwise unpublished content. Irish dance music of the same period, historically a separate study and well documented in Ireland, has been excluded except where it occurs alongside its Scottish equivalent. Dance music from the military pipe manuals, widely popular since the 1930s among Scottish players has already been comprehensively listed and would have doubled the size of the Index, which nevertheless runs to over 12,000 titles.

The Tune Title Index (A-Z) lists the Theme Code (see below), the key and time signatures and the Source Code, which also indicates in how many collections a tune has been published. Example: A1V1P1 stands for AIRD, James, Volume 1, Page 1 and the same pattern follows through the source listing. Where available, further details are given - composer, library source, issue date. The codes are essential to the all-round functioning of the Index.

Additional Search Options The online version has a number of advantages over a printed index. You can download and print out the whole contents of collections and perform word-search and part-title searches. Lists can be assembled of music by time or key signature and can refer to special comments such as occur alongside tunes in the original collections - Slow, Slow Strathspey, Irish, Old, etc. etc. These comments were almost universally excluded by compilers in the later 19th century when so many old strathspeys and reels were re-published.

The Theme Code Index has the primary function of cross-referencing tunes that have acquired more than one title down the years. It reads in numerical sequence from 1-7 for the middle octave; 1L is the lowest listed beat note in the octave below middle C; 1H indicates one octave above and (less frequently) 1T, two octaves above. However many keys the tune has been set in over the years, the key note always has the number 1, so the pattern of the code remains the same. It is based on the Beat Notes of the first two, three, or four bars of the tune: 4 to the bar for common time, 4/4 and 2/2; two to the bar (6/8, 2/4); three to the (3/4), and so on. Special symbols are used to signal the minor mode and accidentals (b, #), and rests (0). Versions of tunes may vary to some degree. The ultimate use for the Theme Code Index is to find a tune of which the melody is remembered but none of its titles. Initially this requires a little practice, jotting down the first bars of the tune and setting the numbers in order, but in most cases it soon becomes a simple routine. For example: The two-part code 3155 551H2H represents one version of one tune, the old song air “Polwart on the Green”. CODE A leads to the area of the list in which it may be found and CODE B completes the identity of the tune. In some cases, there will be other claimants to the code which may include tunes with the same beat notes but a fundamentally different melodic structure. For some reason this has no effect on the efficiency of the system itself.

Anyone wishing to use the Index Online for constructing Theme Codes should go to our Theme Coding page.